The criterion presented in today's blog was known to

Carl Friedrich Gauss in 1796 when he presented his criterion for the constructibility of regular polygons. Even so, the proof of the criteroin was first presented in 1837 by Pierre Laurent Wantzel.

The content in today's blog is taken from Jean-Pierre Tignol's Galois'

Theory of Algebraic Equations.

To simplify the proof, I offer the following postulates.

Postulate 1:

It is possible to draw a line between any two points that are already determined.Posulate 2:

It is possible to draw a circle with a center at a point already determined and with the radius equal to the distance between any two points already determined.Postulate 3:

If two lines are not parallel and not colinear, then they intersect at exactly one point.Postulate 4: If a circle's center is at a point on a line then the circle intersects the extended line at two points.I will now use these postulates to present some lemmas:

Lemma 1: (0,v) is constructible if and only if (v,0) is constructibleProof:

This follows from Postulate 2 above setting center

A at

(0,0) and radius

= v. If

C at

(v,0) is constructible, then we can obtain

B at

(0,v). If

B at

(0,v) is constructible, then we can obtain

C at

(v,0).

QED

Lemma 2: (u,0) is constructible and (0,v) is constructible if and only if (u,v) is constructibleProof:

(1) Assume that

B at

(u,0) and

D at

(0,v) are constructible.

(2) If

B at

(u,0) is constructible and

D at

(0,v) is constructible, then

F at

(u,v) is constructible since:

(a) Let

BG be a line that intersects

B at

(u,0) and is parallel to the y-axis. [Euclid: Book I, Prop 12, see

here]

(b) Let

DE be a line that insersects

D at

(0,v) and is parallel to the x-axis. [Euclid: Book I, Prop 12, see

here]

(c) Then

F at

(u,v) is constructible since it is the point where

BG,DE intersect [See Postulate 3 above]

(4) Assume that

F at

(u,v) is constructible.

(5) Since

F at

(u,v) is constructible, we know that

B at

(u,0) is constructible and

D at

(0,v) is constructible since:

(a) Let

FG be a line parallel to the y-axis that passes through

F at

(u,v) [Euclid: Book I, Prop 12, see

here]

(b) Then

B at

(u,0) is the point where

FG and the x-axis intersect. [See Postulate 3 above]

(c) Let

EF be a line parallel to the x-axis that passes through

F at

(u,v) [Euclid: Book I, Prop 12, see

here]

(d) Then

D at

(0,v) is the point where

EF and the y-axis intersect. [See Postulate 3 above]

QED

Lemma 3:If a line passes through two points

(a1,b1) and

(a2,b2), then it has the equation of form:

αX + βY = γwhere

α = b2 - b1β = a1 - a2γ = a1b2 - b1a2Proof:

(1) This lemma is proved if it can be shown that both points satisfy the equation given.

That is, both equations, lead to

γ = a1b2 - b1a2(2) Case I:

(a1,b1)α(a1) + β(b1) = (b2 - b1)(a1) + (a1 - a2)(b1) = a1b2 - b1a2(3) Case II:

(a2,b2)α(a2) + β(b2) = (b2 - b1)(a2) + (a1 - a2)(b2) = a1b2 - b1a2QED

Lemma 4:If we construct a circle with center

(a1,b1) and radius equal to the distance between

(a2,b2) and

(a3,b3), then it's equation has the form:

X2 + Y2 = αX + βY + γwhere:

α, β, γ are rational expressions of

a1, a2, a3, b1, b2, b3Proof:

(1) The equation for this circle is (see Theorem 1,

here):

(X - a1)2 + (Y - b1)2 = (a2 - a3)2 + (b2 - b3)2(2) Multiplying out the squares involving

X,Y gives us:

X2 - 2a1X + a12 + Y2 - 2b1Y - b12(3) Moving everything but

X2,Y2 to the other side gives us:

X2 + Y2 = 2a1X + 2b1Y + [-a12 -b12 + (a2 - a3)2 + (b2 - b3)2]QED

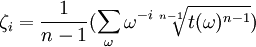

Theorem 5: Criterion of Constructibility Let

O be a circle that with center at

(0,0) and radius

= 1 unit.

The point

(u,v) is constructible from

O if and only if

(u,v) can be obtained from

(1,0) by a sequence of operations of the following types:

(i) rational operations

(ii) extraction of square roots

Proof:

(1) I will prove the first part of the theorem using induction.

(2) For the base case, we assume that

u=a or

0 and

v=a or

0.

(3) To prove the base case, we have four cases to prove:

(a)

(a,0),(0,0) [Constructible from the given]

(b)

(0,a) [Constructible from

(a,0) and Proposition 2 above if we set center at

(0,0) and radius

=a].

(c)

(a,a) [Constructible from (a,0) and Lemma 1 above]

(4) So we assume that all points

(u',v') are constructible.

(5) To complete the first half of the proof, we need to show that if

(u',v') is constructible and

(u,v) is obtained in a single operation from

(u',v'), then

(u,v) is constructible.

(6) Using Lemma 2 above, step #5 is achieved if we show that the following points are constructible:

(u'+v',0)(u' -v',0)(u'v',0)(u'v'-1,0) [assuming

v ≠ 0 ]

(√u',0) [assuming

u ≥ 0]

(7)

(u'+v',0) and

(u' -v',0) are constructible [From Postulate 2 above where the center is

(u',0) and the radius

=v and Postulate 4 above where

(u'-v',0) and

(u'+v',0) are the intersection of the circle and the x-axis.]

(8)

(u'v',0) is constructible since:

(a) We are given that

F at

(0,v') is constructible.

(b) We are given that

C at

(u',0) is constructible.

(c) Let

E at

(0,b) be a point where

b is less than

v' and

b is greater than

0 such that we consider

b our unit of measure (i.e.

b is length

= 1 unit)

(d) Draw a line

EC connecting

E at

(0,b) and

C at

(u',0) [See Posulate 1 above]

(e) Draw a line called

FB parallel to

EC and passing through

F at

(0,v') [Euclid: Book I, Prop 12, see

here]

(f) Let

B at

(z,0) be the point where

FB intersects with the x-axis. [See Postulate 3 above]

(g) Triangles

EAC and

FAB are similar since:

∠ EAC and

∠ FAB are the same.

∠ AEC is congruent to

∠ AFB and

∠ ACE is congruent to

∠ ABF since

FB and

EC are parallel [

Euclid: Book I, Prop 29]

(h) So, we know that:

AC/AE = AB/AF [see Lemma 3,

here]

(i) Since in step #8c above we assumed that

AE = 1 unit, we have:

AC = AB/AFor equivalently:

AB = AF*AC(j) Since the length of

AB is

z [since

A is at

(0,0) and

B is at

(z,0)], the length of

AF is

v' [since

A is at

(0,0) and

F is at

(0,v')] and the length of

AC is

u' [since

A is at

(0,0) and

C is at

(u',0)], it follows that:

z = u'*v'(9)

(u'v'-1,0) is constructible since:

(a) Using the same diagram as step #8 above, we are given that

F at

(0,v') is constructible.

(b) Let us assume that we are given

B at

(u',0) is constructible.

(c) Let

E at

(0,b) be a point where

b is less than

v' and

b is greater than

0 such that we consider

b our unit of measure (i.e.

b is length

= 1 unit)

(d) Draw a line

EC connecting

E at

(0,b) with a point

C at

(c,0) on the x-axis. [Euclid: Book I, Prop 12, see

here]

(e) We can use the same arguments as #8g above to establish that Triangles

EAC and

FAB are similar

(f) Using the same argument as #8i, we have:

AC = AB/AF(g) Since the length of

AB is

u' [since

A is at

(0,0) and

B is at

(u',0)], the length of

AF is

v' [since

A is at

(0,0) and

F is at

(0,v')] and the length of

AC is

c [since

A is at

(0,0) and

C is at

(c,0)], it follows that:

c = u'/v' = u'*v'-1(10) Assuming

u ≥ 0, then

( √u , 0) is constructible since:

(a) Assume that point

B is at

(0,0)(b) Let

D be a point on the x-axis at

(d,0) such that

BD = 1 unit.

(c) Let

C be a point on the x-axis at

(1+u',0) where

1 = BD. [See step #7 above]

(d) Let us a draw a circle

O whose center is at the midpoint

M of

BC and whose radius is

MC. [See Postulate 2 above]

(e) Let

A at

(1,a) be the intersection of

O and a line drawn from

D that is perpendicular to

BC. [Euclid: Book I, Prop 11, see

here]

(f) We can see that triangle

BDA and triangle

ADC are similar since:

Both

∠ BDA and

∠ ADC are right angles

And,

∠ BAC is a right angle [see

Euclid: Book III, Prop 31]

So,

∠ BAD + ∠ DAC = 90 °Since triangle

ADC is a right triangle, we also have

∠ DAC + ∠ DCA = 90 ° [See Lemma 4,

here]

So, we have shown that

∠ BAD ≅ ∠ DCA.

(g) Since the two triangles are equiangular, we have [see Lemma 3,

here]:

DA/BD = DC/DA(h) Since the length of

DA is

c [since

A is at

(1,c) and

D is at

(1,0)], the length of

BD is

1 [since

B is at

(0,0) and

D is at

(1,0)] and the length of

DC is

u' [since

D is at

(1,0) and

C is at

(1+u,0)], it follows that:

c/1 = u'/cFurther, this gives us that:

c2 = u'which means that:

c = √u'(11) To complete the second half of the proof, I will show that if a point

(u,v) can be constructed from

(1,0) then it can be obtained from

(1,0) through a finite sequence of operations.

(12) To accomplish, I need to show that the following imply points obtained from

(1,0):

(a) two lines intersecting

(b) two circles intersecting

(c) line intersecting with a circle

(13) A point at two lines intersecting implies that this new point is obtained from the previous points since:

(a) By Lemma 3 above, the two lines can be represented by:

α1X + β1Y = γ1α2X + β2Y = γ2(b) Assuming that

α1 ≠ 0, we multiply the top equation by

(-α2/α1) and add the two equations together to get:

(-α2/α1)β1Y + β2Y = γ1 + γ2which gives us that:

Y[(-α2/α1)β1 + β2] = γ1 + γ2which shows that

Y can be obtained from the given points.

Y = [γ1 + γ2 ]/[(-α2/α1)β1 + β2](c) Now, all we need to do is show that

X can be obtained from the given points which can be shown using the first equation:

α1X + β1Y = γ1which then shows:

X = (γ1 - β1Y)/(α1)(14) A point at two circles intersecting implies that this new point is obtained from the previous points since:

(a) By Lemma 4 above, the two circles can be represented by:

X2 + Y2 = α1X + β1Y + γ1X2 + Y2 = α2X + β2Y + γ2which gives us:

α1X + β1Y + γ1 = α2X + β2Y + γ2and moving

X to one side and

Y to the other gives us:

α1X - α2X = β2Y - β1Y + γ2 - γ1(b) Now, assuming that

(α1 - α2) ≠ 0, we can state

X in terms of

YX = [(β2 - β1)Y + γ2 - γ1]/(α1 - α2)(c) Now, we can state

Y as a quadratic equation since:

Using:

X2 + Y2 = α1X + β1Y + γ1

We get:

{[(β2 - β1)Y + γ2 - γ1]/(α1 - α2)}2 + Y2 = α1{[(β2 - β1)Y + γ2 - γ1]/(α1 - α2)} + β1Y + γ1(d) Since a quadratic equation is solvable in terms of the coefficients (see Theorem,

here if needed), we have shown that in this case, the points are obtained from the previous points.

(15) A point at a circle intersecting with a line is obtained from the previous points since:

(a) By Lemma 3 above, the line can be represented by:

α1X + β1Y = γ1(b) By Lemma 4 above, the circle can be represented by:

X2 + Y2 = α2X + β2Y + γ2(c) Assuming

α1 ≠ 0, we can restate

X in terms of

Y using step #15a since:

X = (γ1 - β1Y)/α1(d) Substituting into the equation in #15b gives us the following quadratic equation:

([γ1 - β1Y]/α1)2 + Y2 = α2([γ1 - β1Y]/α1) + β2Y + γ2(e) Since a quadratic equation is solvable in terms of the coefficients (see Theorem,

here if needed), we have shown that in this case, the points are obtained from the previous points.

QED

References

, World Scientific, 2001